Differential responses of bumblebee diversity to plant community floral resources and surrounding landscape variables

-

摘要:

以滇西北熊蜂多样性全球分布中心为研究区,在群落花末期选取了香格里拉市境内19个开花植物群落,深入调查了熊蜂及开花植物的多样性。本研究计算了熊蜂的多样性指数,并量化了每个植物群落景观组成和景观配置的多种变量。广义线性模型分析结果显示,总体上熊蜂的多度和物种丰富度与调查群落的花资源密切相关,而熊蜂的香农多样性指数则主要受景观尺度林地覆盖比例的影响。由于不同特性的熊蜂对群落花资源和景观特征的反应可能不同,本研究进一步对不同体型和喙长的熊蜂进行了分析。结果表明,根据飞行能力,大体型的熊蜂对周围林地和耕地覆盖比例的变化更敏感,而中小体型熊蜂更依赖调查群落里的花资源及周围生境间的连通性。从喙长来看,短喙的熊蜂主要依赖调查群落的花资源,而中长喙熊蜂由于其取食策略不同,更依赖景观尺度上的资源。研究结果阐释了花资源的可用性与景观特征对熊蜂多样性的影响式样及其潜在机制,发现飞行能力和觅食策略显著影响了不同熊蜂对环境依赖式样的差异。

Abstract:In this study, we investigated the diversity of bumblebees and their floral resources during the late flowering season across 19 meadows near Shangri-La city in Northwest Yunnan, a renowned global biodiversity hotspot. We calculated the diversity index for bumblebees and measured several variables related to landscape structure and configuration for each meadow. Generalized linear models revealed that bumblebee abundance and species richness were primarily influenced by local floral resources, whereas the Shannon diversity index was largely determined by landscape variables, especially the percentage of woodland coverage. We further analyzed bumblebees with varying body size and tongue length, as these traits may influence responses to local and landscape variables. Notably, large-bodied bumblebees showed greater sensitivity to surrounding landscape variables in relation to flight capabilities, while small- and medium-bodied bumblebees were more dependent on local floral resources and habitat connectivity. Regarding tongue length, short-tongued bumblebees predominantly utilized local floral resources, whereas medium- and long-tongued bumblebees leveraged resources more extensively at the landscape scale, reflecting their different foraging strategies. This study illustrated the significant impact of flower availability and landscape characteristics on bumblebee diversity, highlighting how flight ability and foraging strategy profoundly influence the environmental dependence patterns of different bumblebees.

-

Keywords:

- Bumblebee /

- Diversity /

- Floral resources /

- Landscape scale /

- Bumblebee body size /

- Bumblebee tongue length /

- Late flowering season

-

正常的雌雄配子育性是植物保证后代繁殖的关键因素。对于农作物而言,雌雄配子育性还决定了作物的结实率和产量[1]。雄性不育既是植物最重要的质量性状之一,也是研究水稻(Oryza sativa L.)、小麦(Triticum aestivum L.)、玉米(Zea mays L.)等重要农作物杂种优势利用的基础。目前在水稻、玉米、小麦等作物中利用“三系杂交”的育种方法将雄性不育应用于育种中,极大提高了作物的产量[1-3]。植物雄性育性调控机制已成为近年来杂种优势利用的热门研究方向。

花药和花粉的正常发育是植物雄性繁殖成功的先决条件。从雄蕊原基的形成到花粉粒成熟,直至花药开裂散粉,花药发育受到一系列精细化生物学过程的调控[4]。雄蕊原基细胞经过数轮细胞地分裂和分化,由外至内形成由表皮层、内皮层、中间层和绒毡层4层体细胞包围着花粉母细胞的花药结构。花粉母细胞位于花药室中间,经过减数分裂形成小孢子。小孢子又经过两次不均等的有丝分裂形成成熟的花粉[5]。

1. 植物花药角质层和花粉壁的主要成分

花药和花粉表面分别被花药角质层和花粉壁覆盖,对环境和生物胁迫具有保护作用。花药角质层主要由角质和蜡质组成,角质作为角质层的结构骨架,主要由脂肪酸及其衍生物组成。蜡质围绕在角质的表面,主要由C16 ~ C34脂肪酸及其衍生物组成,包括酯、醛、醇、酮和烷烃[6, 7]。覆盖在成熟花粉粒表面的花粉壁可保护花粉粒不受外界生物或者非生物胁迫损伤,而且能帮助花粉与柱头识别,促进花粉传播[8]。成熟花粉粒的花粉壁由花粉外壁(Exine)、花粉内壁(Intine)和含油层(Tryphine)3层结构组成。花粉壁是一种成分非常复杂的胞外细胞壁基质。目前的研究表明,花粉外壁外层的主要成分是孢粉素,由饱和长链脂肪酸前体或饱和长脂肪链前体经过复杂的生物聚合组成[8, 9]。花粉内壁的成分与普通的细胞壁类似,主要由纤维素、半纤维素和果胶聚合物组成[10]。花粉包被(Pollen coat)或含油层,主要由复杂的脂质、蜡酯、类黄酮、羟肉桂酰基亚精胺代谢产物和蛋白质组成[10]。

角质、蜡质和孢粉素分别是形成花药角质层和花粉外壁的主要成分。研究表明,它们的脂质前体在花药绒毡层细胞中合成,然后被分别转运到花药表面和小孢子表面沉积。前期科学家们通过正向遗传学的手段,分析花药角质层和花粉壁发育缺陷的突变体,鉴定得到一系列蛋白,包括脂质合成酶基因、脂质转运蛋白、转录因子和ABCG转运蛋白等[8, 10, 11]。随着研究的不断深入,大量ABCG转运蛋白被报道参与植物雄性育性调控,本文将系统阐述ABCG转运蛋白参与植物雄性育性调控的功能与机制。

2. ABC转运蛋白的结构特点与分类

ABC转运蛋白又名ATP(Adenosine triphosphate)结合盒式转运蛋白,属于最大的转运蛋白家族。它们广泛存在于微生物到高等植物甚至人类中[12]。ABC转运蛋白属于多结构域的跨膜蛋白,它通过利用自身ATP结合结构域,在Mg2 + 参与下水解ATP获得能量来转运分子,如异生素、激素、糖、氨基酸和离子等[13, 14]。

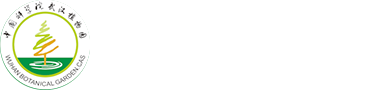

ABC转运蛋白由4个核心结构域组成:两个核苷酸结合结构域(Nucleotide-binding domain,NBD)和两个跨膜结构域(Transmembrane domain,TMD)(图1 :A、B)。根据NBD和TMD的组成可将ABC转运蛋白分为两类,一类是WBC (White/brown complex,WBC)型,其结构包含一个NBD和一个TMD,称为半分子(Half-size)转运蛋白,该类蛋白需要与自身或另外一个半分子转运蛋白结合,形成同源或异源二聚体蛋白发挥转运功能;另一类是PDR(Pleiotropic drug resistance,PDR)型,其结构包含两个NBD和两个TMD,称为全分子(Full-size)转运蛋白,可以单独发挥转运功能[12, 15]。值得一提的是,与其他真核生物ABC转运蛋白不同,植物半分子转运蛋白除了可形成同源二聚体外,还可以与另外的半分子转运蛋白形成异源二聚体[16]。

ABC转运蛋白的NBD和TMD结构域的排布可以是正向(TMD在前,NBD在后,图1:A),也可以是反向(TMD在后,NBD在前,图1:B)。在高等植物中,根据ABC转运蛋白遗传进化特征可分为8个亚族,分别是ABCA(ATP-binding cassette A transporter)至ABCI(ATP-binding cassette Ⅰ transporter),其中ABCH(ATP-binding cassette H transporter)转运蛋白在植物中不存在[17]。ABCA至ABCD(ATP-binding cassette D transporter)亚族蛋白由于TMD位于NBD之前,属于前向转运体[18]。ABCG亚族由于NBD位于TMD之前,属于反向转运体[18, 19]。

植物8个ABC转运蛋白亚族中,ABCG转运蛋白属于最大的一个亚族。在水稻、玉米和拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.)中分别含有50、54和43个成员,其蛋白功能复杂多样[20]。其中拟南芥ABCG蛋白亚族包含28个半分子转运蛋白和15个全分子转运蛋白[17, 21]。随着研究的不断深入,ABCG转运蛋白被报道在植物生殖器官发育、激素运输、角质层形成、次生代谢产物分泌和生物或非生物胁迫响应等方面发挥重要作用[15, 22]。其中,ABCG转运蛋白主要是通过调控植物花粉壁的发育和花药角质层的形成来参与植物雄性育性发育过程[23]。

3. ABCG转运蛋白参与调控植物雄性不育的研究现状

3.1 参与调控花粉壁发育

近年来ABCG转运蛋白被多次研究报道参与转运由绒毡层产生的脂类、酚类、其他孢粉素前体物质以及含油层物质用于花粉壁形成[24]。早期研究发现,拟南芥AtABCG26基因与花粉外壁形成过程中多聚酮化合物的运输相关,该基因功能丧失后会导致植物育性显著降低[25-28]。水稻OsABCG15,又称为PDA1(Post-meitotic deficient anther 1),是AtABCG26的同源基因。pda1突变体由于乌氏体及花粉外壁缺失而导致小孢子败育[29, 30]。最近在玉米中首次报道ZmMS2(Zea mays male sterile2)参与调控花药发育,ZmMS2是OsABCG15和AtABCG26的同源基因,该基因突变后导致小孢子外壁发育不正常[31]。值得一提的是,水稻ABCG15基因突变后,突变体除了不能形成有功能的花粉外壁,其花药角质层发育也存在缺陷。但是拟南芥abcg26突变体的花药角质层发育正常。由此可推测水稻ABCG15可能与多个ABCG半分子转运蛋白相互作用,以运输不同的底物用于花粉外壁和花药角质层的形成。另外,Xu等[32]研究发现,拟南芥中一个bHLH转录因子AMS可以直接结合ABCG26基因启动子上的E-boxes,直接调控ABCG26基因的表达,从而影响花粉外壁的发育。但是目前尚未有研究报道水稻OsABCG15和玉米ZmMS2是否受到转录因子的调控。

早期研究报道拟南芥ABCG1和ABCG16基因参与木栓质和花粉壁细胞外屏障形成。abcg1 abcg16双突变体育性下降,花粉粒干瘪[33, 34]。水稻OsABCG3/LSP1(Less and shrunken pollen 1)是拟南芥ABCG1和ABCG16的同源基因,近期研究发现OsABCG3/LSP1可以转运绒毡层和花粉壁合成的前体物质用于植物生殖发育,该基因功能缺失后会引起花药绒毡层异常降解、花粉外壁内层及花粉内壁层缺失,最终导致植株完全雄性不育[35, 36]。以上研究成果提示,ABCG转运蛋白在不同物种中参与转运花粉壁发育前体物质的功能具有保守性。

此外,ABCG转运蛋白可同时转运多种底物用于植物生长和生殖发育。最新的研究发现,ABCG1和ABCG16除参与转运木栓质和孢粉素前体物质用于花粉发育外,还可影响拟南芥生殖器官中生长素的信号传导。abcg1abcg16双突变体雌蕊中花粉管生长受阻与生长素分布和生长素流动减少有关,此表型可以通过在雌蕊中添加外源生长素得到部分恢复[37]。值得一提的是,目前绝大部分参与植物雄性生殖器官发育的ABCG转运蛋白均属于半分子转运蛋白,关于ABCG全分子转运蛋白参与花药发育的研究报道极少。Choi等[38]研究发现,拟南芥ABCG半分子转运蛋白AtABCG9和ABCG全分子转运蛋白AtABCG31协同参与花粉壁合成。AtABCG9和AtABCG31在绒毡层中高表达,主要通过将特定甾醇糖苷转运到花粉表面用于花粉含油层的沉积,abcg9abcg31双突变体的花粉活力严重下降。

3.2 参与调控花药角质层发育

花药角质层可保护雄配子体免受外界环境影响[39]。角质作为角质层的结构骨架,主要由脂肪酸及其衍生物组成。蜡质主要围绕在角质基质的表面,由C16~C34脂肪酸及其衍生物组成,包括酯、醛、醇、酮和烷烃[6, 7]。

近年来,ABCG转运蛋白被报道参与转运植物角质和蜡质前体从而调控植物发育。Pighin等[40]的研究表明,拟南芥ABCG12/CER5(ECERIFERUM 5)主要从表皮细胞内转运蜡质前体至细胞表面。AtABCG12/CER5基因突变后,突变体茎秆表皮蜡质含量显著降低[40]。拟南芥ABCG11/DSO主要参与转运长链脂肪酸和超长链脂肪酸,该基因突变后,突变体不仅茎秆表面蜡质和角质含量显著性下降,而且突变体花器官脂质沉积和根软木质沉积均下降,突变体植株育性严重受到影响[41, 42]。进一步研究发现,ABCG11自身能形成同源二聚体,也能与ABCG12形成异源二聚体,但是ABCG12不能形成同源二聚体[16]。

与孢粉素前体或脂类物质从绒毡层细胞运输到花药室参与花粉壁的形成相比,绒毡层细胞产生的孢粉素前体或脂类物质如何被运输到花药表面用于花药角质层形成的研究报道较少。水稻ABCG半分子转运蛋白OsABCG26定位于花药表皮、内皮层和Stage 9期的绒毡层中,可将脂质分子从绒毡层转运到花药壁,供角质层发育需要。在osabcg26突变体中可以观察到大量电子致密的脂质颗粒包裹体沿着绒毡层细胞室壁连接至中间层,该现象提示OsABCG26可能主要负责将脂质物质从绒毡层转运到花药壁表面供角质层形成。OsABCG26突变后会导致转运受阻,从而影响角质层形成,导致花粉败育[23, 43]。与OsABCG26蛋白不同,OsABCG15蛋白只定位于绒毡层内侧,并以极性方式面对花药室,因此被认为主要参与花粉外壁形成过程中脂质前体的分配[23]。由于osabcg26osabcg15双突变体的表型能减轻osabcg15单突变体表型,因此推测水稻OsABCG26和OsABCG15是协同调控雄性生殖发育的[23]。

ABCG转运蛋白作为植物大蛋白家族,通过介导脂质代谢,特别是脂质和酚类物质前体在花药层细胞两侧转运以形成花粉发育最重要的两个保护屏障——花粉壁和花药角质层。目前ABCG半分子转运蛋白参与花药发育的研究大部分只停留在表型上的观察,具体的分子机制尚未明确。Zhu等[44]首次研究报道蒺藜苜蓿(Medicago truncatula Gaertn.)ABCG转运蛋白SGE1(Stigma exsertion1)可通过影响花器官中蜡质和角质等长链脂肪酸的运输导致雌雄蕊隔离,形成柱头外露型雄性不育材料。SGE1蛋白可与另一个半分子转运蛋白MtABCG13相互作用,形成一个有功能的异源二聚体。对ABCG蛋白的功能进行深入研究,将有助于阐明其在植物雄性生殖器官发育中的分子机制。

近期,Fang等[45]首次报道玉米一个雄性不育新基因ZmMS13在花药和花粉发育的前期(Stage 5)、中期(Stage 8b)和后期(Stage 10)具有3个表达峰,分别受转录因子ZmbHLH122、ZmMYB84和ZmMYB33-1/-2调控,从而分别影响胼胝质降解、绒毡层程序性死亡和花粉外壁以及花药角质层的形成。该研究首次发现ABCG基因多峰值表达受不同转录因子调控,并阐明其具体的分子机理,拓展了植物ABCG转运蛋白的生物学功能。

表1汇总了目前在玉米、拟南芥和水稻中报道的ABCG转运蛋白参与植物雄性育性调控的研究进展。

表 1 参与植物雄性育性调控的ABCG转运蛋白Table 1. ABCG transporters involved in regulation of plant male fertility物种

Species基因名称

Gene name转运蛋白类型

Transport protein type具体功能

Functions文献

References拟南芥

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.ABCG26/

WBC27半分子 参与花粉外壁形成过程中多聚酮化合物的运输,该基因突变后,花粉外壁发育异常,植株育性显著下降 [25-28] 水稻Oryza sativa L. ABCG15/

PDA1半分子 参与花药角质层、乌氏体及花粉外壁发育 [29, 30] 玉米Zea mays L. MS2 半分子 参与花粉外壁发育,GC-MS分析结果显示ms2突变体花药角质和蜡质单体显著下降 [31] 拟南芥 ABCG1 半分子 参与木栓质和花粉壁细胞外屏障形成,还可影响拟南芥生殖器官中生长素的信号传导 [33, 34, 37] 拟南芥 ABCG16 半分子 参与木栓质和花粉壁细胞外屏障形成,还可影响拟南芥生殖器官中生长素的信号传导 [33, 34, 37] 水稻 OsABCG3/

LSP1半分子 参与转运绒毡层和花粉壁合成的前体物质用于植物生殖发育,该基因功能缺失后会引起花药绒毡层异常降解、花粉外壁内层及花粉内壁层缺失 [35, 36] 拟南芥 ABCG9 半分子 与ABCG31协同将特定甾醇糖苷转运到花粉表面用于花粉含油层的沉积 [38] 拟南芥 ABCG31 全分子 与ABCG9协同将特定甾醇糖苷转运到花粉表面用于花粉含油层的沉积 [38] 拟南芥 ABCG12/

CER5半分子 参与从表皮细胞内转运蜡质前体至细胞表面 [40] 拟南芥 ABCG11/

DSO半分子 转运长链脂肪酸和超长链脂肪酸 [41, 42] 水稻 ABCG26 半分子 主要负责将脂质物质从绒毡层转运到花药壁表面供角质层形成。该基因突变后,突变体花粉外壁及花药角质层发育存在缺陷,还可以影响花粉管伸长 [23, 43] 蒺藜苜蓿

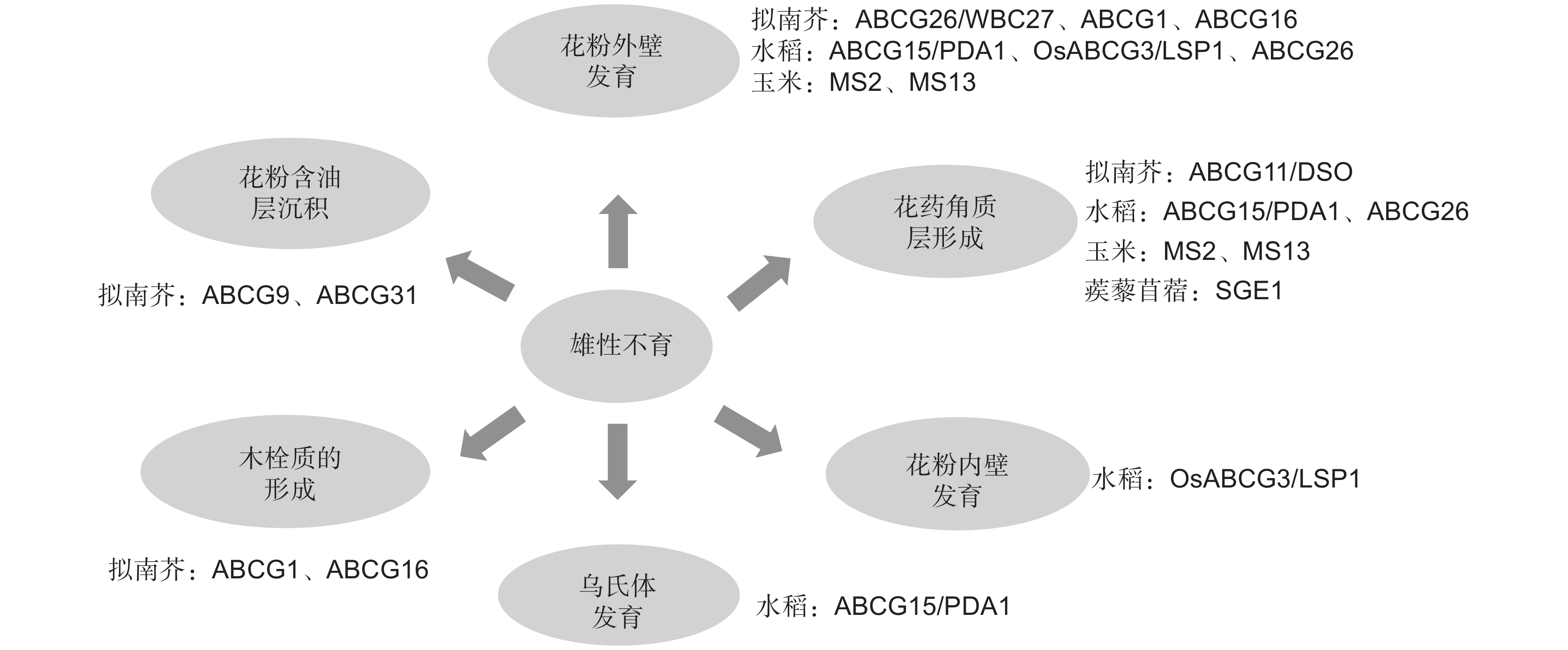

Medicago truncatula Gaertn.SGE1 半分子 影响蒺藜苜蓿花器官中蜡质和角质等长链脂肪酸的运输 [44] 玉米 ZmMS13 半分子 影响胼胝质降解、绒毡层程序性死亡和花粉外壁以及花药角质层的形成 [45] 拟南芥 ABCG28 半分子 将多胺和活性氧定位于正在生长的花粉管尖端 [46] 最新的研究发现,拟南芥AtABCG28在成熟花粉和生长的花粉管中特异表达,该蛋白定位于分泌囊泡膜上。当AtABCG28基因突变后,花粉管生长缺陷,无法将多胺和活性氧定位于正在生长的花粉管尖端,植株表现为完全雄性不育[46]。图2总结和归纳了目前研究中主要的ABCG转运蛋白参与植物雄性育性调控的具体功能。

4. 展望

ABCG作为ABC转运蛋白最大的一个亚族,参与植物发育中各种生理过程。本文首先概述了植物花药角质层和花粉壁的主要成分,其次总结了ABC转运蛋白的结构特点,最后重点阐述ABCG转运蛋白参与调控植物花药和花粉发育的具体功能。随着研究不断深入,ABCG转运蛋白参与植物雄性育性调控的功能不再局限于调控花药角质层和花粉外壁的发育。

虽然ABCG转运蛋白的研究报道较多,但是其具体转运的底物尚未研究清楚。目前对于ABCG转运蛋白功能的研究主要采用反向遗传学的方法,通过气相色谱-质谱联用仪(GC-MS)分析ABCG突变体和野生型的特定部位组织的代谢产物差异,对ABCG转运蛋白的底物或者底物类别做出合理的猜测。目前在拟南芥、水稻、玉米等植物中大部分的ABCG转运蛋白底物均是该方法预测的[23, 38, 45]。此外,根据ABCG转运蛋白的特点,目前最直接有效的ABCG转运底物鉴定方法是通过一个转运实验以严格的ATP依赖的方式证明其跨膜转运活性。该转运实验的先决条件是将ABCG转运蛋白在适当的系统中进行过表达,如烟草(Nicotiana tabacum L.)原生质体系统或者酵母菌株(YMM12和BY-2)细胞系[20]。目前拟南芥ABCG转运蛋白的底物可通过体内同位素标记实验进行检测。例如,通过烟草原生质体系统构建的转运实验鉴定拟南芥ABCG11和ABCG32可以转运10,16-二羟基、C16∶0-2甘油和W-OH C16∶0等角质前体用于植物角质层形成[22]。但是用同位素标记进行实验鉴定ABCG转运蛋白的底物非常耗时,且许多同位素化合物尚未商业化,因此阻碍了该技术的利用。除此之外,基于使用双光子显微镜的研究结果表明,聚酮化合物是拟南芥ABCG26的底物。当AtABCG26基因突变后,突变体在绒毡层细胞中积累了大的荧光液泡,小孢子中的荧光丧失。当AtABCG26基因和编码孢粉素聚酮化合物生物合成代谢基因构建双突变体(atabcg26 acos5(acyl coenzyme A synthetase5)、atabcg26 tkpr1)以及三突变体(atabcg26 pksa(polyketide synthase a) pksb),这些双突变体和三突变体花药绒毡层细胞并未观察到荧光液泡内含物[28]。因此,可以推测AtABCG26将聚酮化合物从绒毡层细胞转运到花粉壁形成孢粉素骨架。

目前ABCG家族蛋白参与植物花药发育的报道集中于对ABCG半分子转运蛋白的研究。ABCG半分子转运蛋白需要通过同源或者异源二聚体的方式形成一个有功能的ABCG转运蛋白。通过寻找与其他ABCG共表达的基因,或者通过酵母筛库,或者质谱等方式鉴定ABCG转运蛋白的潜在伴侣,并研究其分子生物学功能,可拓宽ABCG转运蛋白参与植物雄性育性调控的具体分子机制。由于ABCG转运蛋白在不同植物中具有保守性,因此其同源基因在其他作物中可能也发挥类似的作用,通过反向遗传学的方法,例如利用基因编辑,可加深我们对ABCG转运蛋白在多种植物中的功能机制的了解。而所获得的雄性不育等优良性状的突变系在杂交作物育种和种子生产中具有广泛的应用前景。

2 1,2)如需查阅附图内容请登录《植物科学学报》网站(http://www.plantscience.cn)查看本期文章。1 1~3)如需查阅附表内容请登录《植物科学学报》网站(http://www.plantscience.cn)查看本期文章。3 1~5)如需查阅附表内容请登录《植物科学学报》网站( http://www.plantscience.cn)查看本期文章。 -

表 1 19个样地的基本信息。

Table 1 Information on 19 study sites.

样地

Site纬度

Latitude经度

Longitude海拔

Elevation / m面积

Area / m2S1 27.3462°N 99.8933°E 2 935 1 244 S2 27.4140°N 99.8530°E 3 307 15 448 S3 27.6947°N 99.7264°E 3 268 2 179 S4 27.8504°N 99.6843°E 3 323 1 323 S5 27.7697°N 99.6755°E 3 303 4 143 S6 28.0321°N 99.7786°E 3 138 1 549 S7 27.3655°N 99.9342°E 2 747 2 085 S8 27.6129°N 99.8045°E 3 288 1 584 S9 27.8976°N 99.6291°E 3 289 1 632 S10 27.4252°N 99.8468°E 3 230 9 198 S11 27.8257°N 99.7415°E 3 341 4 260 S12 27.6756°N 99.7356°E 3 242 4 906 S13 27.5414°N 99.8068°E 3 168 554 S14 27.8183°N 99.7206°E 3 297 2 484 S15 27.8570°N 99.7187°E 3 286 13 012 S16 27.6001°N 99.7179°E 3 296 4 123 S17 27.5627°N 99.7950°E 3 223 1 653 S18 27.9788°N 99.7302°E 3 503 3 054 S19 27.8647°N 99.6729°E 3 295 693 表 2 不同特性熊蜂的分类

Table 2 Classification of Bombus species with different characteristics

熊蜂物种

Bombus标本数Ns 平均翅基距离

Mean ITD

(Mean±SD) / mmLog(平均翅基距离)Log(Mean ITD) 体型Body size 标本数Ni 平均喙长

Mean tongue length

(Mean±SD) / mmLog(平均喙长)Log(Mean tongue length) 喙长

Tongue length标本数Nt 安韦熊蜂

B. avanus Skorikov10 3.76±0.25 0.58 小 10 7.47±0.86 0.87 短 9 小雅熊蜂

B. remotus Skorikov5 3.67±0.53 0.56 小 10 6.43±0.64 0.81 短 5 疏熊蜂

B. remotus Tkalcu16 3.92±0.21 0.59 小 16 9.22±0.70 0.96 中 15 兴熊蜂

B. impetuosus Smith28 3.99±0.26 0.60 小 28 8.73±0.67 0.94 中 16 灰熊蜂

B. graham Frison5 4.96±0.38 0.70 中 16 8.73±0.51 0.94 中 12 南熊蜂

B. secures Frison112 4.74±0.38 0.68 中 112 14.67±1.86 1.17 长 14 桔尾熊蜂

B. friseanus Skorikov350 4.75±0.39 0.68 中 348 7.82±0.83 0.89 短 132 砖葬熊蜂

B. funerarius Smith3 4.52±0.25 0.66 中 26 12.95±1.18 1.11 长 27 颂杰熊蜂

B. nobilis Friese16 5.42±0.36 0.73 大 16 14.02±0.73 1.15 长 9 长翅熊蜂

B. longipennis Friese2 5.41±0.35 0.73 大 10 7.04±0.42 0.85 短 10 白背熊蜂

B. festivus Smith3 5.59±0.39 0.75 大 8 8.80±0.57 0.94 中 5 注:Ns,调查标本总数;Ni,翅基距离被测标本数量;Nt,喙长被测标本数量。 Notes: Ns, number of total measured specimens; Ni, number of measured specimens of intertegular distance (ITD); Nt, number of measured specimens of tongue length. -

[1] Potts SG,Imperatriz-Fonseca V,Ngo HT,Aizen MA,Biesmeijer JC,et al. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being[J]. Nature,2016,540(7632):220−229.

[2] An JD,Huang JX,Shao YQ,Zhang SW,Wang B,et al. The bumblebees of North China(Apidae,Bombus latreille)[J]. Zootaxa,2014,3830(1):1−89.

[3] Nayak RK,Rana K,Bairwa VK,Singh P,Bharthi VD. A review on role of bumblebee pollination in fruits and vegetables[J]. J Pharmacogn Phytochem,2020,9(3):1328−1334.

[4] Dicks LV,Breeze TD,Ngo HT,Senapathi D,An JD,et al. A global-scale expert assessment of drivers and risks associated with pollinator decline[J]. Nat Ecol Evol,2021,5(10):1453−1461.

[5] Cameron SA,Sadd BM. Global trends in bumble bee health[J]. Annu Rev Entomol,2020,65:209−232.

[6] Sárospataki M,Bakos R,Horváth A,Neidert D,Horváth V,et al. The role of local and landscape level factors in determining bumblebee abundance and richness[J]. Acta Zool Acad Sci Hung,2016,62(4):387−407.

[7] Jackson HB,Fahrig L. Are ecologists conducting research at the optimal scale?[J]. Glob Ecol Biogeogr,2015,24(1):52−63.

[8] Diaz-Forero I,Kuusemets V,Mänd M,Liivamägi A,Kaart T,Luig J. Influence of local and landscape factors on bumblebees in semi-natural meadows:a multiple-scale study in a forested landscape[J]. J Insect Conserv,2013,17(1):113−125.

[9] Roulston TAH,Goodell K. The role of resources and risks in regulating wild bee populations[J]. Annu Rev Entomol,2011,56:293−312.

[10] Hyjazie BF,Sargent RD. Floral resources predict the local bee community:implications for conservation[J]. Biol Conserv,2022,273(9):109679.

[11] Kremen C,Williams NM,Aizen MA,Gemmill-Herren B,Lebuhn G,et al. Pollination and other ecosystem services produced by mobile organisms:a conceptual framework for the effects of land-use change[J]. Ecol Lett,2007,10(4):299−314.

[12] Carvell C,Bourke AFG,Dreier S,Freeman SN,Hulmes S,et al. Bumblebee family lineage survival is enhanced in high-quality landscapes[J]. Nature,2017,543(7646):547−549.

[13] Timberlake TP,Vaughan IP,Baude M,Memmott J. Bumblebee colony density on farmland is influenced by late-summer nectar supply and garden cover[J]. J Appl Ecol,2021,58(5):1006−1016.

[14] Mola JM,Hemberger J,Kochanski J,Richardson LL,Pearse IS. The Importance of forests in bumble bee biology and conservation[J]. BioScience,2021,71(12):1234−1248.

[15] Riggi LGA,Lundin O,Berggren Å. Mass-flowering red clover crops have positive effects on bumblebee richness and diversity after bloom[J]. Basic Appl Ecol,2021,56(7):22−31.

[16] Kallioniemi E,Åström J,Rusch GM,Dahle S,Åström S,Gjershaug JO. Local resources,linear elements and mass-flowering crops determine bumblebee occurrences in moderately intensified farmlands[J]. Agric Ecosyst Environ,2017,239(4):90−100.

[17] Neumüller U,Burger H,Krausch S,Blüthgen N,Ayasse M. Interactions of local habitat type,landscape composition and flower availability moderate wild bee communities[J]. Landsc Ecol,2020,35(10):2209−2224.

[18] Persson AS,Smith HG. Seasonal persistence of bumblebee populations is affected by landscape context[J]. Agric,Ecosyst Environ,2013,165(2):201−209.

[19] Greenleaf SS,Williams NM,Winfree R,Kremen C. Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size[J]. Oecologia,2007,153(3):589−596.

[20] Westphal C,Steffan-Dewenter I,Tscharntke T. Bumblebees experience landscapes at different spatial scales:possible implications for coexistence[J]. Oecologia,2006,149(2):289−300.

[21] Gómez-Martínez C,Aase ALTO,Totland Ø,Rodríguez-Pérez J,Birkemoe T,et al. Forest fragmentation modifies the composition of bumblebee communities and modulates their trophic and competitive interactions for pollination[J]. Sci Rep,2020,10(1):10872.

[22] Theodorou P,Baltz LM,Paxton RJ,Soro A. Urbanization is associated with shifts in bumblebee body size,with cascading effects on pollination[J]. Evol Appl,2021,14(1):53−68.

[23] Jauker B,Krauss J,Jauker F,Steffan-Dewenter I. Linking life history traits to pollinator loss in fragmented calcareous grasslands[J]. Landsc Ecol,2013,28(1):107−120.

[24] Gérard M,Marshall L,Martinet B,Michez D. Impact of landscape fragmentation and climate change on body size variation of bumblebees during the last century[J]. Ecography,2021,44(2):255−264.

[25] Inouye DW. The effect of proboscis and corolla tube lengths on patterns and rates of flower visitation by bumblebees[J]. Oecologia,1980,45(2):197−201.

[26] Huang JX,An JD,Wu J,Williams PH. Extreme food-plant specialisation in Megabombus bumblebees as a product of long tongues combined with short nesting seasons[J]. PLoS One,2015,10(8):e0132358.

[27] Walcher R,Karrer J,Sachslehner L,Bohner A,Pachinger B,et al. Diversity of bumblebees,heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers maintained by both:abandonment and extensive management of mountain meadows in three regions across the Austrian and Swiss Alps[J]. Landsc Ecol,2017,32(10):1937−1951.

[28] 梁铖,张学文,黄家兴,宋文菲,张红,等. 云南熊蜂地理区划及物种多样性分析[J]. 应用昆虫学报,2018,55(6):1045−1053. Liang C,Zhang XW,Huang JX,Song WF,Zhang H,et al. Biogeography and species diversity of bumblebees in Yunnan,Southwest China[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology,2018,55(6):1045−1053.

[29] 刘乐怡,杨双娜,张龙,宋钰红. 基于土地利用演变的生态敏感性评价——以香格里拉市为例[J]. 西部林业科学,2021,50(6):124−131. Liu LY,Yang SN,Zhang L,Song YH. Evaluation of ecological sensitivity based on the evolution of land use:taking Shangri-La city as an example[J]. Journal of West China Forestry Science,2021,50(6):124−131.

[30] Ahmad M,Uniyal SK,Batish DR,Rathee S,Sharma P,Singh HP. Flower phenological events and duration pattern is influenced by temperature and elevation in Dhauladhar mountain range of Lesser Himalaya[J]. Ecol Indic,2021,129(10):107902.

[31] Laha S,Chatterjee S,Das A,Smith B,Basu P. Exploring the importance of floral resources and functional trait compatibility for maintaining bee fauna in tropical agricultural landscapes[J]. J Insect Conserv,2020,24(3):431−443.

[32] Hsieh TC,Ma KH,Chao A. iNEXT:an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity(Hill numbers)[J]. Methods Ecol Evol,2016,7(12):1451−1456.

[33] Chao A,Gotelli NJ,Hsieh TC,Sander EL,Ma KH,Colwell RK,et al. Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers:a framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies[J]. Ecol Monogr,2014,84(1):45−67.

[34] Roswell M,Dushoff J,Winfree R. A conceptual guide to measuring species diversity[J]. Oikos,2021,130(3):321−338.

[35] 梁欢. 滇西北高山草甸植物——熊蜂传粉网络研究[D]. 北京:中国科学院大学,2020:18−19. [36] Oksanen J,Blanchet FG,Kindt R,Legendre P,Minchin P R,O’hara R, et al. Vegan:community ecology package. R package version 2.5-7[DB/OL]. [2023-08-01]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

[37] Ebeling A,Klein AM,Schumacher J,Weisser WW,Tscharntke T. How does plant richness affect pollinator richness and temporal stability of flower visits?[J]. Oikos,2008,117(12):1808−1815.

[38] Baldock KCR,Goddard MA,Hicks DM,Kunin WE,Mitschunas N,et al. Where is the UK's pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects[J]. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci,2015,282(1803):20142849.

[39] Geslin B,Baude M,Mallard F,Dajoz I. Effect of local spatial plant distribution and conspecific density on bumble bee foraging behaviour[J]. Ecol Entomol,2014,39(3):334−342.

[40] Holland JD,Bert DG,Fahrig L. Determining the spatial scale of species' response to habitat[J]. BioScience,2004,54(3):227−233.

[41] González-Césped C,Alaniz AJ,Vergara PM,Chiappa E,Zamorano J,Mandujano V. Effects of urban environmental conditions and landscape structure on taxonomic and functional groups of insects[J]. Urban For Urban Green,2021,58(2):126902.

[42] Hagen M,Wikelski M,Kissling WD. Space use of bumblebees (Bombus spp.) revealed by radio-tracking[J]. PLoS One,2011,6(5):e19997.

[43] Phan TN,Kuch V,Lehnert LW. Land cover classification using Google Earth Engine and random forest classifier-the role of image composition[J]. Remote Sens,2020,12(15):2411.

[44] McGarigal K. FRAGSTATS help[M]. Massachusetts:University of Massachusetts,2015:182.

[45] Maurer C,Sutter L,Martínez-Núñez C,Pellissier L,Albrecht M. Different types of semi-natural habitat are required to sustain diverse wild bee communities across agricultural landscapes[J]. J Appl Ecol,2022,59(10):2604−2615.

[46] Baguette M,van Dyck H. Landscape connectivity and animal behavior:functional grain as a key determinant for dispersal[J]. Landsc Ecol,2007,22(8):1117−1129.

[47] Freemark K,Bert D,Villard MA. Patch-,landscape-,and regional-scale effects on biota[M]// Gutzwiller KJ,ed. Applying Landscape Ecology in Biological Conservation. New York:Springer,2002:58−83.

[48] Graf LV,Schneiberg I,Gonçalves RB. Bee functional groups respond to vegetation cover and landscape diversity in a Brazilian metropolis[J]. Lands Ecol,2022,37(4):1075−1089.

[49] Miguet P,Jackson HB,Jackson ND,Martin AE,Fahrig L. What determines the spatial extent of landscape effects on species?[J]. Landsc Ecol,2016,31(6):1177−1194.

[50] Calcagno V,de Mazancourt C. Glmulti:an R package for easy automated model selection with (generalized) linear models[J]. J Stat Softw,2010,34(12):1−29.

[51] Bartoń K. MuMIn:multi-model inference. R package version 1.46.0[DB/OL]. [2024-01-01]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn.

[52] Burnham KP,Anderson DR,Huyvaert KP. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology:some background,observations,and comparisons[J]. Behav Ecol Sociobiol,2011,65(1):23−35.

[53] Wickham H. ggplot2:elegant graphics for data analysis[DB/OL]. [2023-08-10]. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

[54] R Core Team. R:a language and environment for statistical computing[DB/OL]. [2023-01-01].https://www.R-project.org/.

[55] Kennedy CM,Lonsdorf E,Neel MC,Williams NM,Ricketts TH,et al. A global quantitative synthesis of local and landscape effects on wild bee pollinators in agroecosystems[J]. Ecol Lett,2013,16(5):584−599.

[56] Moquet L,Bacchetta R,Laurent E,Jacquemart AL. Spatial and temporal variations in floral resource availability affect bumblebee communities in heathlands[J]. Biodivers Conserv,2017,26(3):687−702.

[57] Kaluza BF,Wallace HM,Heard TA,Minden V,Klein A,Leonhardt SD. Social bees are fitter in more biodiverse environments[J]. Sci Rep,2018,8(1):12353.

[58] Vaudo AD,Tooker JF,Grozinger CM,Patch HM. Bee nutrition and floral resource restoration[J]. Curr Opin Insect Sci,2015,10(4):133−141.

[59] Pyke GH. Local geographic distributions of bumblebees near Crested Butte,Colorado:competition and community structure[J]. Ecology,1982,63(2):555−573.

[60] Gutiérrez-Chacón C,Dormann CF,Klein AM. Forest-edge associated bees benefit from the proportion of tropical forest regardless of its edge length[J]. Biol Conserv,2018,220(4):149−160.

[61] Sõber V,Leps M,Kaasik A,Mänd M,Teder T. Forest proximity supports bumblebee species richness and abundance in hemi-boreal agricultural landscape[J]. Agric Ecosyst Envi ron,2020,298(12):106961.

[62] Rivers-Moore J,Andrieu E,Vialatte A,Ouin A. Wooded semi-natural habitats complement permanent grasslands in supporting wild bee diversity in agricultural landscapes[J]. Insects,2020,11(11):812.

[63] Svensson B,Lagerlöf J,Svensson BG. Habitat preferences of nest-seeking bumble bees (Hymenoptera:Apidae) in an agricultural landscape[J]. Agricu Ecosyst Environ,2000,77(3):247−255.

[64] Kells AR,Goulson D. Preferred nesting sites of bumblebee queens (Hymenoptera:Apidae) in agroecosystems in the UK[J]. Biol Conserv,2003,109(2):165−174.

[65] Liczner AR,Colla SR. A systematic review of the nesting and overwintering habitat of bumble bees globally[J]. J Insect Conserv,2019,23(5-6):787−801.

[66] Boscolo D,Tokumoto PM,Ferreira PA,Ribeiro JW,Santos JSD. Positive responses of flower visiting bees to landscape heterogeneity depend on functional connectivity levels[J]. Perspecti Ecol Conserv,2017,15(1):18−24.

[67] Jha S,Kremen C. Resource diversity and landscape-level homogeneity drive native bee foraging[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2013,110(2):555−558.

[68] Pope NS,Jha S. Seasonal food scarcity prompts long-distance foraging by a wild social bee[J]. Am Nat,2018,191(1):45−57.

[69] Del Castillo RC,Sanabria-Urbán S,Serrano-Meneses MA. Trade-offs in the evolution of bumblebee colony and body size:a comparative analysis[J]. Ecol Evol,2015,5(18):3914−3926.

[70] Kreyer D,Oed A,Walther-Hellwig K,Frankl R. Are forests potential landscape barriers for foraging bumblebees? Landscape scale experiments with Bombus terrestris agg. and Bombus pascuorum (Hymenoptera,Apidae)[J]. Biol Conserv,2004,116(1):111−118.

[71] Vray S,Rollin O,Rasmont P,Dufrêne M,Michez D,Dendoncker N. A century of local changes in bumblebee communities and landscape composition in Belgium[J]. J Insect Conserv,2019,23(3):489−501.

[72] Hemberger J,Crossley MS,Gratton C. Historical decrease in agricultural landscape diversity is associated with shifts in bumble bee species occurrence[J]. Ecol Lett,2021,24(9):1800−1813.

[73] Abudulai M,Nboyine JA,Quandahor P,Seidu A,Traore F. Agricultural intensification causes decline in insect biodiversity[M]. London:IntechOpen,2022:1−198.

[74] Goulson D,Nicholls E,Botías C,Rotheray EL. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites,pesticides,and lack of flowers[J]. Science,2015,347(6229):1255957.

[75] 马如彪,程峰,易邦进,付磊,蒋莲芳. 香格里拉土地利用垂直分异分析[J]. 云南师范大学学报,2011,31(6):70−75. Ma RB,Cheng F,Yi BJ,Fu L,Jiang LF. Vertical differentiation of land-use in Shangri-La[J]. Journal of Yunnan Normal University,2011,31(6):70−75.

[76] Gérard M,Martinet B,Maebe K,Marshall L,Smagghe G,et al. Shift in size of bumblebee queens over the last century[J]. Glob Change Biol,2020,26(3):1185−1195.

[77] Walther-Hellwig K,Frankl R. Foraging habitats and foraging distances of bumblebees,Bombus spp. (Hym. ,Apidae),in an agricultural landscape[J]. J Appl Entomol,2000,124(7-8):299−306.

-

其他相关附件

-

PDF格式

李月华附件 点击下载(1302KB)

-

下载:

下载: