Assessing microbial diversity in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. based on high-throughput sequencing

-

摘要:

果树具有较高的经济价值,并大多依赖传粉者实现繁殖成功以保证产量。花药微生物能影响植物的花粉活力,其组成也可能受到传粉者访问的影响;理解花药微生物的多样性和群落构建模式对于提高果树的繁殖适合度具有潜在意义,但目前相关研究仍相对缺乏。本研究基于高通量测序技术分析了传粉者访问前(套袋组)与访问后(访问组)枇杷(Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl.)花药中真菌与细菌的组成及差异。结果显示,传粉者访问未显著改变花药微生物的多样性及组成,套袋组中优势真菌科为枝孢菌科与球腔菌科,访问组优势真菌科则为枝孢菌科与梅奇酵母科。此外,两组中优势细菌科均为产碱杆菌科与欧文菌科。研究结果表明,枇杷花药微生物具有相对稳定的群落结构,传粉者不是驱动花药微生物群落构建的主要因素。

Abstract:Fruit trees, vital to global agriculture, depend heavily on pollinators to facilitate successful reproduction and ensure optimal yield. Microorganisms associated with anthers can influence pollen viability, and their community composition may be affected by pollinator activity. While understanding the diversity and community assembly patterns of these microorganisms has potential implications for enhancing the reproductive fitness of fruit trees, research in this area remains relatively scarce. This study employed high-throughput sequencing to analyze the diversity and community structure of fungi and bacteria on the anthers of loquat (Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl.) before (bagged group) and after (nature group) pollinator visitation. Results showed that pollinator visitation had no significant effect on the diversity or composition of anther microbiomes. In the bagged group, dominant fungal taxa included Cladosporiaceae and Mycosphaerellaceae, whereas Cladosporiaceae and Metschnikowiaceae were dominant in the nature group. Bacterial communities in both groups were also dominated by Alcaligenaceae and Erwiniaceae. These findings indicate that the microbial community composition within loquat anthers is inherently stable and largely unaffected by pollinator activity.

-

-

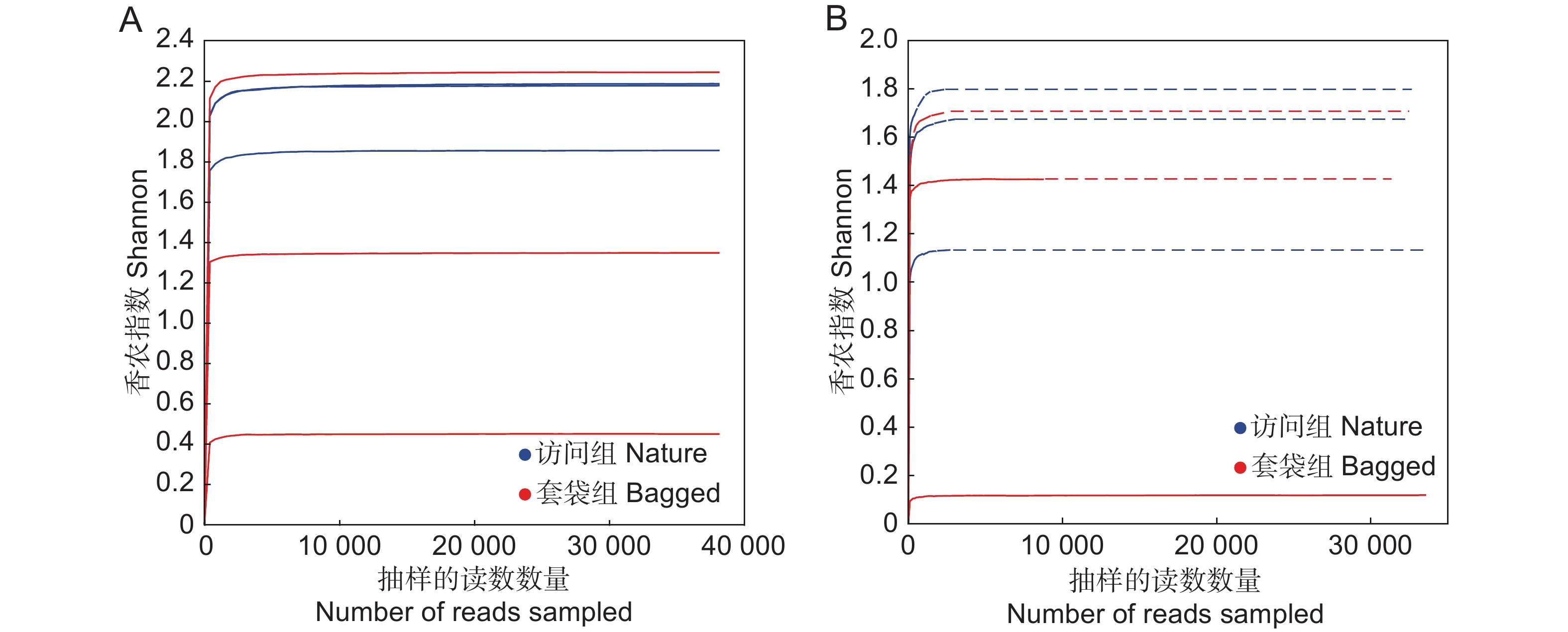

图 1 枇杷花药微生物群落稀释曲线

基于香农指数(Shannon)展示枇杷套袋组(红色)与访问组(蓝色)花药真菌(A)与细菌(B)群落的稀释曲线。

Figure 1. Rarefaction curves of microbial community in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica based on Shannon index

Rarefaction curves based on Shannon index, showing fungal (A) and bacterial (B) diversity in bagged (red) and nature (blue) groups.

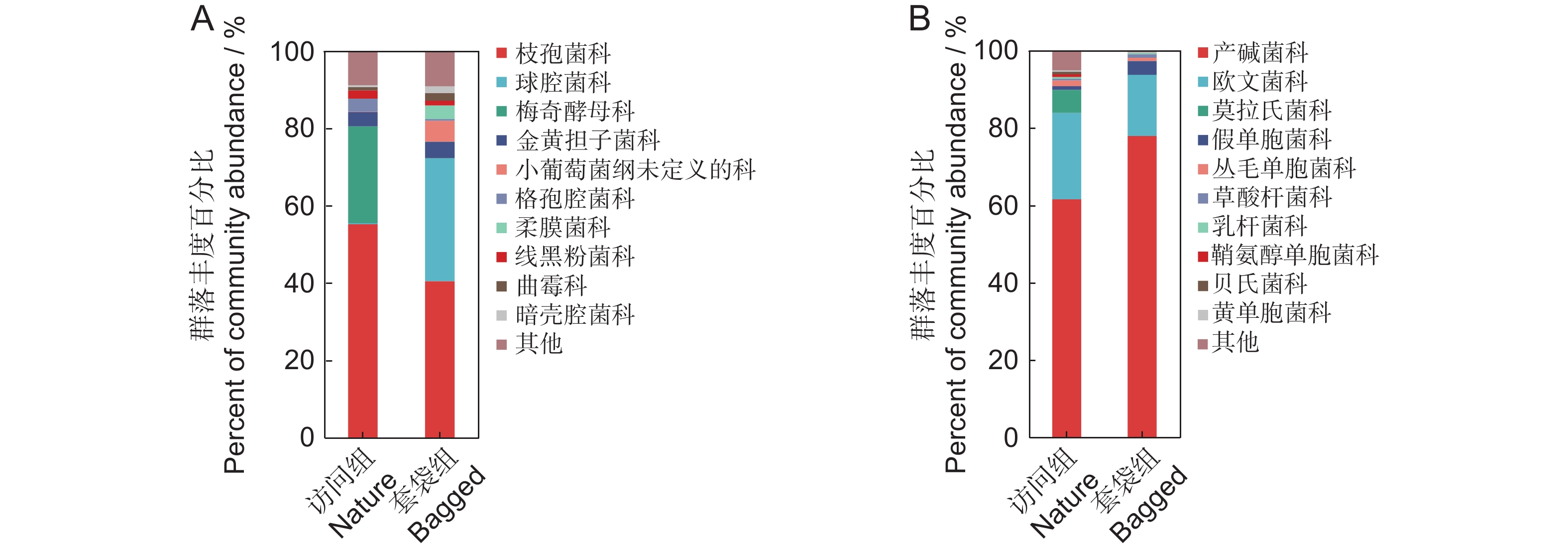

图 2 枇杷花药微生物群落结构(科水平)

A:以ITS2测序表征的平均丰度>1%的套袋组与访问组真菌科组成;B:以16S测序表征的平均丰度>1%的套袋组与访问组细菌科组成。图中仅展示各实验组中丰度占比前10的微生物,其余物种合并为“其他”。

Figure 2. Structure of microbial community in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica (family level)

A: Composition of fungal families with an average abundance greater than 1%, characterized by ITS2 sequencing, in nature and bagged groups; B: Composition of bacterial families with an average abundance greater than 1%, characterized by 16S sequencing, in nature and bagged groups. Only the top 10 most abundant microbes in each experimental group are shown in the figure, with all other species combined under “Others”.

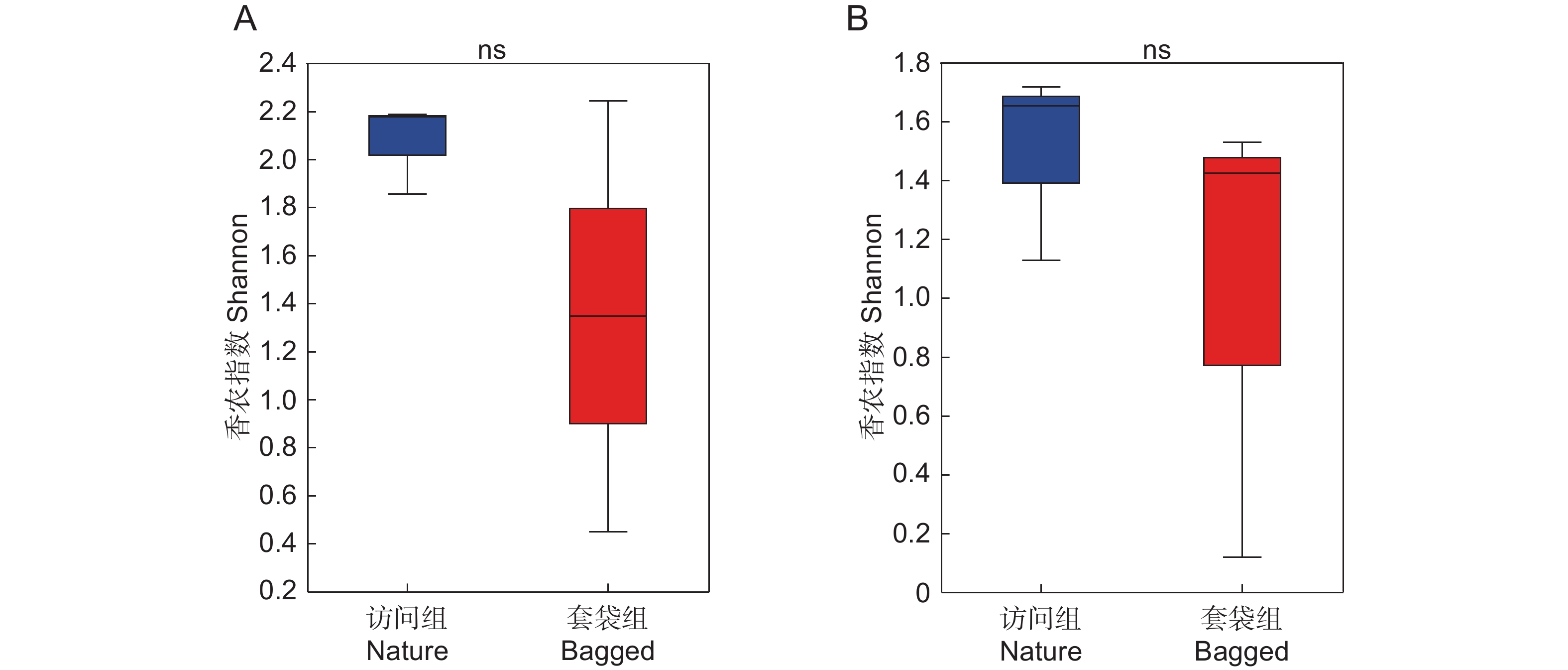

图 3 枇杷花药微生物Alpha多样性分析(Shannon指数)

基于香农指数展示枇杷访问组(蓝色)与套袋组(红色)花药真菌(A)与细菌(B)的Alpha多样性。利用Wilcoxon秩和检验比较两个实验组中真菌与细菌Alpha多样性的差异,箱线图显示了中值和四分位距,ns表示两个实验组间不存在显著差异。

Figure 3. Alpha diversity analysis (Shannon index) of microbial community in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica

Alpha diversity of fungal (A) and bacterial (B) communities in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica in nature (blue) and bagged (red) groups is presented based on Shannon index. Differences in fungal and bacterial alpha diversity between two experimental groups were assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Boxplot illustrates median and interquartile range, with “ns” signifying no significant difference.

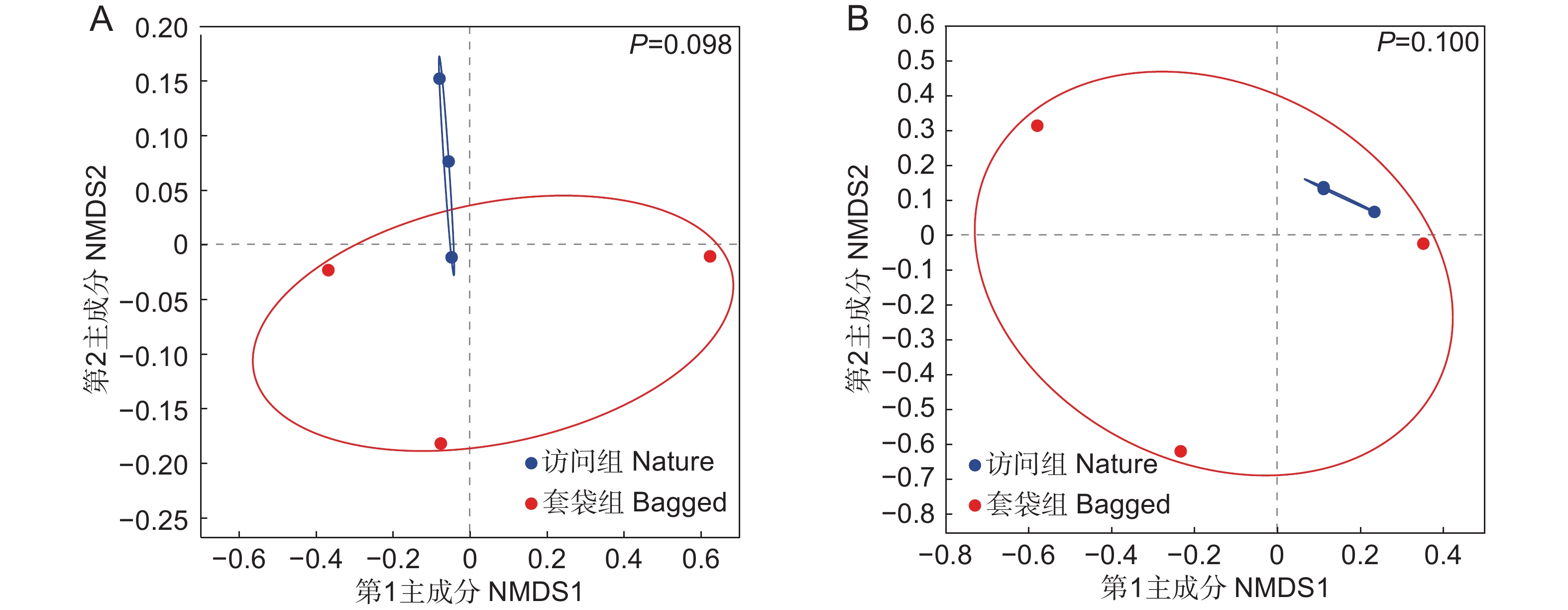

图 4 枇杷花药微生物群落的NMDS分析

基于Bray-Curtis距离对枇杷花药微生物群落进行非度量多维尺度(NMDS)排序,对真菌(A)和细菌(B)进行了单独排序。蓝色实心圆圈代表访问组样本,红色实心圆圈代表套袋组样本。绘制分组椭圆展示样本点之间的分布情况。基于Bray-Curtis距离算法,利用PERMANOVA比较套袋组与访问组真菌与细菌群落组成,P<0.05表示具有显著差异。

Figure 4. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of microbial community in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination of microbial communities in anthers of Eriobotrya japonica based on Bray-Curtis distance was performed, with separate analyses for fungi (A) and bacteria (B). Blue solid circles represent samples from nature group, red solid circles represent samples from bagged group. Group ellipses are drawn to present distribution of sample points. Based on Bray-Curtis distance algorithm, PERMANOVA was used to compare fungal and bacterial community compositions between bagged and nature groups, with P<0.05 indicating significant differences.

表 1 使用不同距离算法的PERMANOVA分析汇总

Table 1 Summary of permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using different distance algorithms

Group df Bray-Curtis Unweighted-UniFrac Weighted-UniFrac F R2 P F R2 P F R2 P 真菌 1 1.423 0.262 0.098 1.387 0.257 0.100 1.233 0.236 0.200 细菌 1 2.167 0.351 0.100 0.991 0.198 0.500 0.473 0.106 0.900 -

[1] Theodorou P,Radzevičiūtė R,Lentendu G,Kahnt B,Husemann M,et al. Urban areas as hotspots for bees and pollination but not a panacea for all insects[J]. Nat Commun,2020,11(1):576. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14496-6

[2] Didham RK,Basset Y,Collins CM,Leather SR,Littlewood NA,et al. Interpreting insect declines:seven challenges and a way forward[J]. Insect Conserv Diver,2020,13(2):103−114. doi: 10.1111/icad.12408

[3] Hallmann CA,Sorg M,Jongejans E,Siepel H,Hofland N,et al. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas[J]. PLoS One,2017,12(10):e0185809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185809

[4] Sánchez-Bayo F,Wyckhuys KAG. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna:a review of its drivers[J]. Biol Conserv,2019,232:8−27. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.020

[5] Lister BC,Garcia A. Climate-driven declines in arthropod abundance restructure a rainforest food web[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2018,115(44):E10397−E10406.

[6] Tong ZY,Wu LY,Feng HH,Zhang M,Armbruster WS,et al. New calculations indicate that 90% of flowering plant species are animal-pollinated[J]. Natl Sci Rev,2023,10(10):nwad219. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwad219

[7] Steffan SA,Dharampal PS,Kueneman JG,Keller A,Argueta-Guzmán MP,et al. Microbes,the 'silent third partners' of bee-angiosperm mutualisms[J]. Trends Ecol Evol,2024,39(1):65−77. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2023.09.001

[8] Kwon Y,Lee JT,Kim HS,Jeon C,Kwak YS. Comparative tomato flower and pollinator hive microbial communities[J]. J Plant Dis Prot,2018,125(1):115−119. doi: 10.1007/s41348-017-0090-z

[9] Eisdcowitch D,Kevan PG,Lachance MA. The nectar-inhabiting yeasts and their effect on pollen germination in common milkweed,Asclepias syriaca L.[J]. Isr J Bot,1990,39(1-2):217−225.

[10] Eisikowitch D,Lachance MA,Kevan PG,Willis S,Collins-Thompson DL. The effect of the natural assemblage of microorganisms and selected strains of the yeast Metschnikowia reukaufii in controlling the germination of pollen of the common milkweed Asclepias syriaca[J]. Can J Bot,1990,68(5):1163−1165. doi: 10.1139/b90-147

[11] Christensen SM,Munkres I,Vannette RL. Nectar bacteria stimulate pollen germination and bursting to enhance microbial fitness[J]. Curr Biol,2021,31(19):4373−4380.

[12] Canto A,Herrera CM,Medrano M,Pérez R,García IM. Pollinator foraging modifies nectar sugar composition in Helleborus foetidus (Ranunculaceae):an experimental test[J]. Am J Bot,2008,95(3):315−320. doi: 10.3732/ajb.95.3.315

[13] Peay KG,Belisle M,Fukami T. Phylogenetic relatedness predicts priority effects in nectar yeast communities[J]. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci,2012,279(1729):749−758.

[14] Rering CC,Beck JJ,Hall GW,McCartney MM,Vannette RL. Nectar-inhabiting microorganisms influence nectar volatile composition and attractiveness to a generalist pollinator[J]. New Phytol,2018,220(3):750−759. doi: 10.1111/nph.14809

[15] Yang M,Deng GC,Gong YB,Huang SQ. Nectar yeasts enhance the interaction between Clematis akebioides and its bumblebee pollinator[J]. Plant Biol,2019,21(4):732−737. doi: 10.1111/plb.12957

[16] Herrera CM,de Vega C,Canto A,Pozo MI. Yeasts in floral nectar:a quantitative survey[J]. Ann Bot,2009,103(9):1415−1423. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp026

[17] Shade A,McManus PS,Handelsman J. Unexpected diversity during community succession in the apple flower microbiome[J]. Mbio,2013,4(2):e00602−12.

[18] Aleklett K,Hart M,Shade A. The microbial ecology of flowers:an emerging frontier in phyllosphere research[J]. Botany,2014,92(4):253−266. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2013-0166

[19] Canto A,Herrera CM,Rodriguez R. Nectar-living yeasts of a tropical host plant community:diversity and effects on community-wide floral nectar traits[J]. PeerJ,2017,5:e3517. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3517

[20] Von Arx M,Moore A,Davidowitz G,Arnold AE. Diversity and distribution of microbial communities in floral nectar of two night-blooming plants of the Sonoran desert[J]. PLoS One,2019,14(12):e0225309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225309

[21] De Vega C,Álvarez-Pérez S,Albaladejo RG,Steenhuisen SL,Lachance MA,et al. The role of plant-pollinator interactions in structuring nectar microbial communities[J]. J Ecol,2021,109(9):3379−3395. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13726

[22] Vorholt JA. Microbial life in the phyllosphere[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol,2012,10(12):828−840. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2910

[23] Rebolleda Gómez M,Ashman TL. Floral organs act as environmental filters and interact with pollinators to structure the yellow monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus) floral microbiome[J]. Mol Ecol,2019,28(23):5155−5171. doi: 10.1111/mec.15280

[24] Russell AL,Rebolleda-Gómez M,Shaible TM,Ashman TL. Movers and shakers:bumble bee foraging behavior shapes the dispersal of microbes among and within flowers[J]. Ecosphere,2019,10(5):e02714. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2714

[25] 周肖霄,张彦文,赵骥民,李竹月. 花部微生物生态学研究进展[J]. 植物科学学报,2023,41(1):121−127. doi: 10.11913/PSJ.2095-0837.22036 Zhou XX,Zhang YW,Zhao JM,Li ZY. Advances in floral microbial ecology[J]. Plant Science Journal,2023,41(1):121−127. doi: 10.11913/PSJ.2095-0837.22036

[26] Cariñanos P,Casares-Porcel M. Urban green zones and related pollen allergy:a review. Some guidelines for designing spaces with low allergy impact[J]. Landscape Urban Plann,2011,101(3):205−214. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.03.006

[27] Oldenburg M,Petersen A,Baur X. Maize pollen is an important allergen in occupationally exposed workers[J]. J Occup Med Toxicol,2011,6:32. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-6-32

[28] Abbate JL,Gladieux P,Hood ME,de Vienne DM,Antonovics J,et al. Co-occurrence among three divergent plant-castrating fungi in the same silene host species[J]. Mol Ecol,2018,27(16):3357−3370. doi: 10.1111/mec.14805

[29] Hartmann FE,Rodríguez de la Vega RC,Carpentier F,Gladieux P,Cornille A,et al. Understanding adaptation,coevolution,host specialization,and mating system in castrating anther-smut fungi by combining population and comparative genomics[J]. Annu Rev Phytopathol,2019,57:431−457. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-095947

[30] Alexander HM. Epidemiology of anther-smut infection of Silene alba caused by Ustilago violacea:patterns of spore deposition and disease incidence[J]. J Ecol,1990,78(1):166−179. doi: 10.2307/2261043

[31] Jennersten O. Insect dispersal of fungal disease:effects of Ustilago infection on pollinator attraction in Viscaria vulgaris[J]. Oikos,1988,51(2):163−170. doi: 10.2307/3565638

[32] Curran HR,Roets F,Dreyer LL. Anther-smut fungal infection of South African Oxalis species:spatial distribution patterns and impacts on host fecundity[J]. South Afr J Bot,2009,75(4):807−815. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2009.08.004

[33] Ambika Manirajan B,Ratering S,Rusch V,Schwiertz A,Geissler-Plaum R,et al. Bacterial microbiota associated with flower pollen is influenced by pollination type,and shows a high degree of diversity and species-specificity[J]. Environ Microbiol,2016,18(12):5161−5174. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13524

[34] Fang Q,Chen YZ,Huang SQ. Generalist passerine pollination of a winter-flowering fruit tree in central China[J]. Ann Bot,2012,109(2):379−384. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr293

[35] 蔡平,包立军,相入丽,张璐. 中国枇杷主要病害发生规律及综合防治[J]. 中国南方果树,2005,34(3):47−50. [36] 王继廉,李玉花. 枇杷病虫害防治要点[J]. 云南农业,2016(1):37−38. [37] Pozo MI,Herrera CM,Bazaga P. Species richness of yeast communities in floral nectar of southern Spanish plants[J]. Microbiol Ecol,2011,61(1):82−91. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9682-x

[38] Pozo MI,Lachance MA,Herrera CM. Nectar yeasts of two southern Spanish plants:the roles of immigration and physiological traits in community assembly[J]. FEMS Microbiol Ecol,2012,80(2):281−293. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01286.x

[39] Smessaert J,van Geel M,Verreth C,Crauwels S,Honnay O,et al. Temporal and spatial variation in bacterial communities of "Jonagold" apple (Malus×domestica Borkh.) and "Conference" pear (Pyrus communis L.) floral nectar[J]. MicrobiologyOpen,2019,8(12):e918. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.918

[40] Rering CC,Rudolph AB,Li QB,Read QD,Muñoz PR,et al. A quantitative survey of the blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) culturable nectar microbiome:variation between cultivars,locations,and farm management approaches[J]. FEMS Microbiol Ecol,2024,100(3):fiae020. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiae020

[41] Pozo MI,Herrera CM,Alonso C. Spatial and temporal distribution patterns of nectar-inhabiting yeasts:how different floral microenvironments arise in winter-blooming Helleborus foetidus[J]. Fungal Ecol,2014,11:173−180. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2014.06.007

[42] Toju H,Vannette RL,Gauthier MPL,Dhami MK,Fukami T. Priority effects can persist across floral generations in nectar microbial metacommunities[J]. Oikos,2018,127(3):345−352. doi: 10.1111/oik.04243

[43] Zemenick AT,Rosenheim JA,Vannette RL. Legitimate visitors and nectar robbers of Aquilegia formosa have different effects on nectar bacterial communities[J]. Ecosphere,2018,9(10):e02459. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2459

[44] Vokou D,Vareli K,Zarali E,Karamanoli K,Constantinidou HIA,et al. Exploring biodiversity in the bacterial community of the mediterranean phyllosphere and its relationship with airborne bacteria[J]. Microb Ecol,2012,64(3):714−724. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0053-7

[45] Herrera CM,Canto A,Pozo MI,Bazaga P. Inhospitable sweetness:nectar filtering of pollinator-borne inocula leads to impoverished,phylogenetically clustered yeast communities[J]. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci,2010,277(1682):747−754.

[46] Junker RR,Keller A. Microhabitat heterogeneity across leaves and flower organs promotes bacterial diversity[J]. FEMS Microbiol Ecol,2015,91(9):fiv097. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv097

[47] Kosenko VN. Contributions to the pollen morphology and taxonomy of the Liliaceae[J]. Grana,1999,38(1):20−30. doi: 10.1080/001731300750044672

[48] Debray R,Herbert RA,Jaffe AL,Crits-Christoph A,Power ME,Koskella B. Priority effects in microbiome assembly[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol,2022,20(2):109−121. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00604-w

[49] Dhami MK,Hartwig T,Fukami T. Genetic basis of priority effects:insights from nectar yeast[J]. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci,2016,283(1840):20161455.

[50] Wilson M,Lindow SE. Coexistence among epiphytic bacterial populations mediated through nutritional resource partitioning[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol,1994,60(12):4468−4477. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4468-4477.1994

[51] Belisle M,Peay KG,Fukami T. Flowers as islands:spatial distribution of nectar-inhabiting microfungi among plants of Mimulus aurantiacus,a Hummingbird-pollinated shrub[J]. Microb Ecol,2012,63(4):711−718. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9975-8

[52] Hendry TA,Ligon RA,Besler KR,Fay RL,Smee MR. Visual detection and avoidance of pathogenic bacteria by Aphids[J]. Curr Biol,2018,28(19):3158−3164. e4.

[53] Rering CC,Vannette RL,Schaeffer RN,Beck JJ. Microbial co-occurrence in floral nectar affects metabolites and attractiveness to a generalist pollinator[J]. J Chem Ecol,2020,46(8):659−667. doi: 10.1007/s10886-020-01169-3

[54] Russell AL,Ashman TL. Associative learning of flowers by generalist bumble bees can be mediated by microbes on the petals[J]. Behav Ecol,2019,30(3):746−755. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arz011

[55] Schaeffer RN,Rering CC,Maalouf I,Beck JJ,Vannette RL. Microbial metabolites elicit distinct olfactory and gustatory preferences in bumblebees[J]. Biol Lett,2019,15(7):20190132. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2019.0132

[56] Morris MM,Frixione NJ,Burkert AC,Dinsdale EA,Vannette RL. Microbial abundance,composition,and function in nectar are shaped by flower visitor identity[J]. FEMS Microbiol Ecol,2020,96(3):fiaa003. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa003

[57] Allard SM,Ottesen AR,Brown EW,Micallef SA. Insect exclusion limits variation in bacterial microbiomes of tomato flowers and fruit[J]. J Appl Microbiol,2018,125(6):1749−1760. doi: 10.1111/jam.14087

下载:

下载: